Alicia Simon Nappy News Black Beauty, black, white, women, relaxing, dyeing, Black Hair Care, Dye vs Perm, Black Hair 0

Many years ago, when I was a member of the popular hair site Naturally Curly, I participated in a discussion thread about what it means to be “naturally curly.” Many black women who posted to the thread commented on the increase in members who were chemically altering their hair with “natural” products such as Naturalaxer and BodiPhier. Those of us, myself included, who wear our Afro-textured hair chemically unaltered attempted to address our beliefs with regards to whether there was a “need” for chemical alteration of tightly curled hair for “manageability,” as well as whether someone who chemically altered their texture could be said to be “naturally curly.”

Many years ago, when I was a member of the popular hair site Naturally Curly, I participated in a discussion thread about what it means to be “naturally curly.” Many black women who posted to the thread commented on the increase in members who were chemically altering their hair with “natural” products such as Naturalaxer and BodiPhier. Those of us, myself included, who wear our Afro-textured hair chemically unaltered attempted to address our beliefs with regards to whether there was a “need” for chemical alteration of tightly curled hair for “manageability,” as well as whether someone who chemically altered their texture could be said to be “naturally curly.”

It wasn’t the first time this subject had come up on Naturally Curly, which to this day hosts members of all races. Every time it did appear during my time there, at least one non-black person (usually a white person) would innocently ask why straightening or chemically altering hair evoked such heated debate among black women. This essay evolved from a very long post that attempted to answer the question. In it, I present a comparative scenario based on the belief that white women are allowed to change their hair without a lot of drama. I published the original version of this essay on my now-defunct site, Hair Food for Thought, in 2003. The Nappturality version presented here contains a few changes from the original, but I believe that the basic argument is still sound. You be the judge.

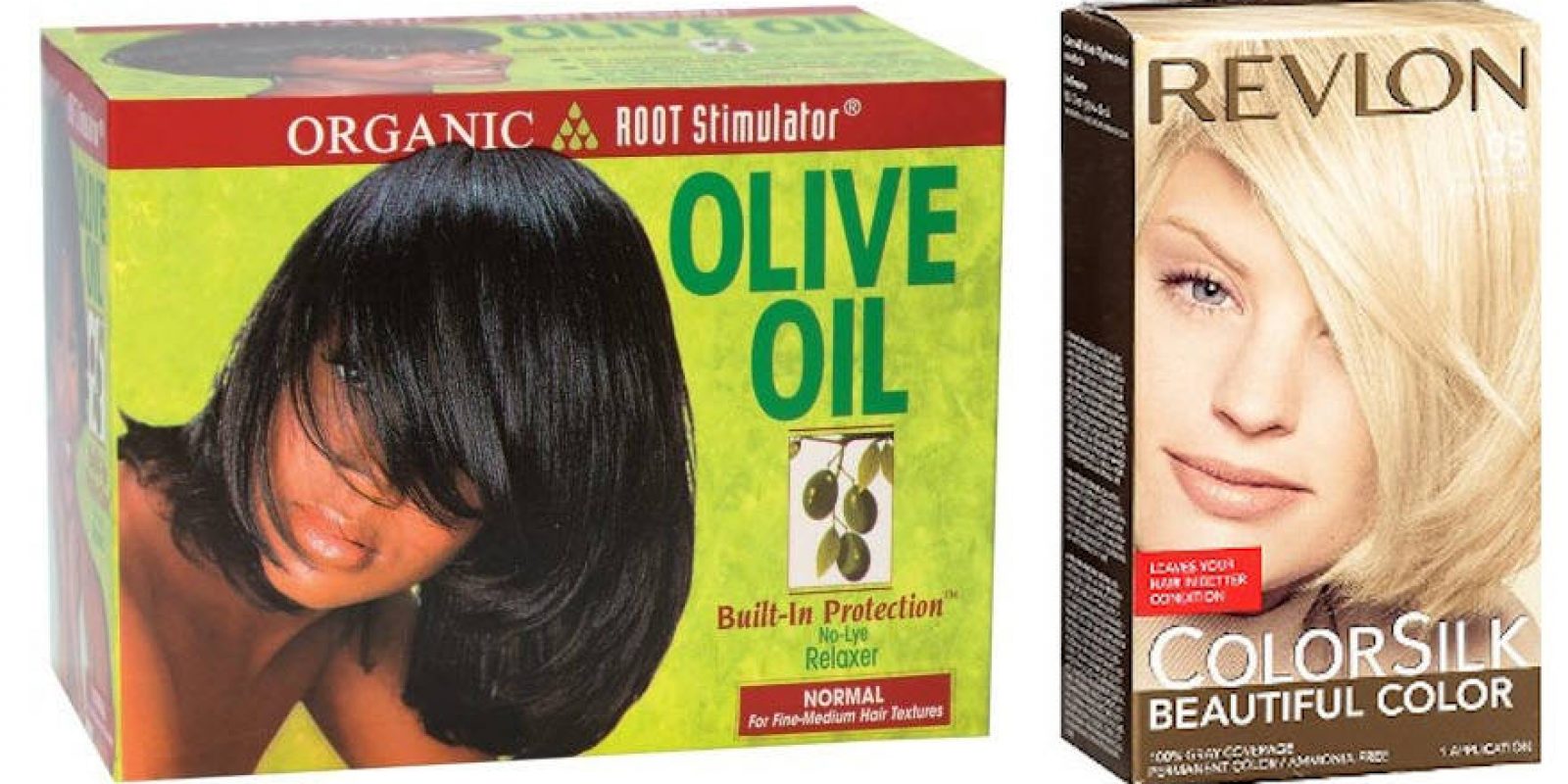

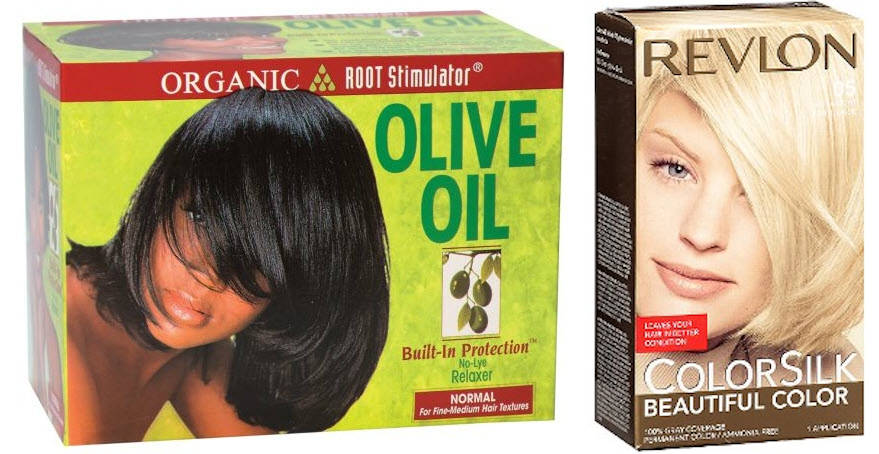

For the purposes of this scenario, I’m going to equate black women’s relaxing their Afro-textured hair straight with white women’s dyeing their dark hair blonde. I know this is a very broad stroke, but understand that what I’m trying to describe is an alternate universe. It’s not a perfect comparison by any means, and I’m leaving certain things out, most notably the history behind this behavior, which I’ll go into at the end of this essay. I wrote this merely to give non-black people a general idea of what it means for a black woman to chemically alter her hair texture or to leave her texture unaltered.

Keep in mind that some of the following points are true for white women in the real world…but black women relaxing their Afro-textured hair would be the same as white women dyeing their dark hair blonde only if all of the following were true.

Although the majority of white women have naturally medium brown, dark brown, red, or black hair growing from their scalps, 70-80 percent of those women dye their hair blonde, without a break, for years, often from puberty until death. For the purposes of this scenario, I’m going to describe these women as “bleached women.”

Many children, boys and girls, come out of the womb with blonde hair, but in most cases (not all) the hair color darkens over time. Some mothers wonder anxiously if their baby’s blonde strands will stay blonde or if they’ll “turn.” Some mothers go through unusual lengths to keep a child’s blonde strands, or employ folk recipes (which generally don’t work) to ensure that they will give birth to a child with blonde hair.

Going to extra lengths to create or maintain loose texture in babies’ hair isn’t very common in the black community, but it’s not unheard of.

Girls and women (as well as boys and men) with naturally light hair are generally seen as having “good” hair, and are generally considered prettier and “luckier” because of their hair.

If you identify as black and have straight, wavy, or loosely curled hair, it is assumed that you got that hair from one or more non-black ancestors. This is why “good” hair is also described as “mixed people’s hair,” as in “racially mixed.” What many people, regardless of race, refer to as “black,” “African,” or “African-American” hair is Afro-textured hair, which happens to be the most common hair type amongst members of many African ethnic groups. However, it’s not uncommon to hear statements made that suggest that all native-born Africans have Afro-textured hair, that this has been the case for centuries, and that if you are the product of a union between a black and a non-black, you are automatically “supposed” to have straight, wavy, or loosely curled hair.

Girls are taught from a very early age, consciously and subconsciously, that blonde or light hair is better than dark hair and that dark hair is a “problem” that needs to be “fixed.”

In terms of the basics of daily hair care—washing, combing, etc.—color doesn’t make nearly as much a difference as texture, so I admit this isn’t a clean comparison. However, the basic truth is this: From childhood, most black women have been conditioned away from learning how to care for natural Afro-textured hair largely because of a belief that anything other than Afro-textured hair—regardless of whether they’re born with it or whether they get it out of a bottle or jar—is “better,” “easier,” and “prettier.”

Some mothers of dark-haired daughters begin dyeing their daughters’ hair blonde as early as two or three years old.

I had my first relaxer put in when I was five. Fortunately my mother saw the damage it did and allowed it to grow out.

Parents, specifically mothers, of little girls whose dark hair isn’t bleached or otherwise disguised or covered up, wholly or partially (e.g. blonde extensions, hair colored “at least” a dark blonde, head coverings) are seen as unusual – either they’re “militant” or “lazy” or somehow aren’t doing what they should be doing for their daughters.

Let me stress here that most black parents I personally know don’t believe in chemically altering a daughter’s hair before a certain age. Most of the time the hair is lightly heat-straightened, combed out into puffs or braids, or hidden with braid extensions or even a weave or wig. However, in most parts of America, you will rarely see a little black girl with natural, unaltered, loose, authentically Afro-textured hair in the playground. Thankfully, this is starting to change…a little. One thing I’ve noticed in the last few years is that when I see a little black girl with natural Afro-textured hair cut into a short ‘fro, usually she’s accompanied by at least one white adoptive parent. The Jolie-Pitts aren’t unique in this regard.

The hair care industry sells specially-designed bleach kits “just for little girls.”

The vast majority of little girls used as actresses in TV commercials, TV shows, and movies have light hair – either natural or bleached.

This too is starting to change…a little. It is no secret that Madison Avenue, which dictates much of what’s considered fashionable and media-appropriate, is located in New York City, which is one of the few cities in America where women wearing natural Afro-textured hair are not uncommon or, at least, not uncommon to the point of notice or stigma.

Most dolls, particularly fashion dolls like Barbie, have varying shades of blonde hair. Every once in a while you will see a doll with red, brown or black hair, but usually that doll is passed up in favor of its blonde-haired counterparts. This is because by the time the girl is old enough to play with fashion dolls, she has most likely absorbed the notion—seen all over the media and most likely echoed by members of her own family and community—that blonde hair is better than dark hair.

While doll manufacturers discuss the value of “hair play” as a design consideration, it’s a marker of the dominant hair culture that they consider straight hair the only texture that girls can play with or are interested in playing with.

By puberty most dark-haired girls bleach their hair.

When I was young, getting your hair relaxed was a sign that you were growing up, and it usually corresponded with entering middle school and/or puberty. Considering the fact that children’s relaxers exist, I don’t know if this belief is still widely held.

It is generally believed that if you are a woman and you want to get a decent job, particularly in corporate America, your hair must be blonde. Dark-haired college seniors who may have experimented with growing or cutting their bleached hair out are encouraged by career counselors and other older adults to return to bleaching.

It is generally believed that bleaching dark hair makes the hair somehow “better,” even though statistics exist that show the negative effects of long-term bleaching. Women are aware of these statistics, yet they continue bleaching. Some women go in search of a “natural” bleach that will allow them to avoid the stigma of dark hair and avoid the hair damage as well. Alternately, they’ll resort to hair extensions, wigs and weaves to give them the appearance of blonde hair. Shops that sell wigs and extension and weave hair proliferate. Because dark-haired women have been conditioned to think of dark hair as difficult, most of them have no clue how to “handle” dark hair or make it look its best.

It is not uncommon to see women with hair that’s been damaged by “overbleaching” (thinning hairline, ragged ends, lack of body, lack of volume, just to name a few side effects). If they acknowledge the damage, they’ll often chalk it up to how hard it is to have dark hair, as though bleaching is the only “cure” available. Conversely, some women are able to bleach their hair for years without experiencing any significant visual damage to the hair as a result. Credit for this is usually given first to the women’s stylists and/or their genetic history, and only after those factors have been observed might the women’s daily regimens come into play as a possible factor.

Most hair care products aimed at naturally dark-haired women focus on bleaching and keeping the hair healthy while bleaching. Many products are designed to minimize or prevent the negative effects associated with long-term bleaching and “overbleaching.” The vast majority of hair advertisements in women’s magazines focus on these products.

In this scenario, I presume that white people are in the majority. If they weren’t, there would most likely be a specially-labeled products section in drugstores and department stores. The general assumption would be that only the products in this section would “work” on bleached hair and that all the other products in the hair aisle wouldn’t.

Most schools of cosmetology, when they address dark hair, focus almost exclusively on bleaching the dark hair and caring for and styling it in its bleached state.

Most dark-haired women go to salons to have their hair bleached and their roots touched up. Again, because dark hair is stigmatized, bleached women don’t like to go too long without a touch-up or else they don’t feel or look “right.” And because the majority of women have naturally dark hair, and the majority of those dark-haired women bleach, hair salons do big business. Because stylists know that women will do just about anything to avoid having to “deal” or be seen with dark hair, they have no problem cramming women into their appointment books and making them wait for several hours, because they know the women would rather spend half a day in the salon than be caught in public with dark roots. Some women avoid long salon waits by doing their own touch-ups at home, but they do this knowing that there is a risk of overbleaching.

It is generally believed that most men prefer light hair on women.

Although there exist men who have naturally blonde hair, and there exist a few dark-haired men who bleach their hair, most dark-haired men do not alter their natural color and don’t experience any significant adverse social or cultural effects as a result (except for possibly being passed over as marriage prospects by some women; see next point).

Currently texturizing is making a comeback among black men, for reasons that some claim are similar to those black women give for relaxing. However, if every black man decided to go back to natural hair tomorrow, the impact would not be anywhere near as great as it would be if black women did the same thing.

Some women (and men) purposely look for and marry men (and women) with naturally blonde hair in hopes of having children with naturally light or blonde hair. If the man or woman has dark hair, they might be hoping to “better” the genetic line. If the man or woman has blonde hair, they might be hoping to “keep the hair in the family.” Some families encourage and support this type of “homegrown genetic tinkering”…and have done so for generations.

Again, it’s not like this is very common in the black community, but it’s not unheard of. Plus, you don’t need to be a biologist to know that sometimes this kind of tinkering works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

Older women who are no longer considered sexually available or desirable will sometimes stop bleaching their hair and let it grow out in its natural color (gray, red, brown, black, or a mixture). Some older women simply replace the bleach with blonde wigs that they wear in public and/or for special occasions. These women usually have spent their entire lives avoiding their dark hair and are incapable of seeing dark hair as anything other than undesirable.

I have personally witnessed, and have also heard of, instances where elderly black women in the hospital were ashamed to let (usually white) doctors see them with unaltered Afro-textured hair. I don’t want to judge them too harshly because I understand the history behind their actions. I touch on this history later in this essay.

Women who decide to stop bleaching their dark hair after bleaching it continuously for years worry about the ramifications of doing so. Some of their fears include:

Reactions from co-workers, family and friends

Not knowing how to care for the hair as it grows out (again, this is based on the general belief that bleaching the hair makes it “easier to deal with”)

Their “hire-ability” (if they don’t have a job already)

Their professional image (if they have a job)

Their attractiveness (regardless of whether they have a man)

For many women, these fears prevent them from putting down the bleach.

Some women who, despite these fears, decide to stop bleaching their dark hair find that their fears become reality. Family members, friends, and co-workers ask, “When are you going to do something to your hair?” Husbands and boyfriends turn their noses up at the new dark hair. They are often expected to bleach their hair, or at least wear some sort of fake blonde hair, for “special occasions.” There is little information available on how to make dark hair look its best. The average hairstylist, having largely been trained in bleaching hair and styling bleached hair to its best advantage, is of little or no help, often suggesting a “light bleach job” to “help” with the transition.

I should say here that when I cut my relaxed hair off, in 1995, I didn’t get a lot of overt negative reactions. Either people offered compliments or they had the good manners not to say anything rude to my face. My immediate family, which has always been fairly open-minded (not to mention pro-black), was very supportive of my decision. In the years I’ve discussed hair on the Internet with other black women, I’m finding that my experience is the exception to the rule, particularly in cases where the natural hair is not loosely curled; see next point.

After many years of bleaching, some dark-haired women are surprised to discover that their natural hair color isn’t as dark as they thought it was. These women often receive comments such as, “Well, if my hair looked like yours, I’d go natural too.” Not surprisingly, those with the darkest hair colors find themselves having to justify their going natural to people who simply can’t understand why they’d want to “make themselves ugly on purpose.” Women who wear dark hair are questioned about their mental health, their diet, and their sexual preference, among other things.

Often, women who are having difficulty caring for their dark hair, or can’t deal with the negative reactions they’re receiving from other people, or are still carrying in their minds the belief that their hair is just “not as good” in its natural state, resort to “blanching.” which is not as harsh as an actual bleaching. They may also choose dark extensions, a dark-haired wig, or a “temporary dark rinse” so they can have the natural “look”—or they may go back to bleaching even though usually they have not given themselves the time to unlearn many years of anti-dark hair programming.

Dark-haired women who choose to wear their hair naturally create support groups (online and face-to-face) to help each other learn to care for and appreciate their natural dark hair. As they begin to realize that their hair isn’t ugly or difficult or otherwise bad, and that, contrary to belief, their hair is often healthier without the regular bleach applications, they begin to question the whole culture behind bleaching.

Dark-haired women sometimes receive support and envy from bleached women who say, “I wish I could do that.” (The unspoken message is, “I wish I had the courage to do that.”) Some bleached women are encouraged to go natural when they see dark-haired women wearing their hair proudly and well.

Dark hair begins to be recognized in places where it never was before, such as the corporate office, and on TV and in movies.

Natural Afro-textured hair has become far more visible in the 21st Century, both in the media and in real life. Although some people still think it’s a fad, I believe that many of us who are natural aren’t doing it for fashion. As I’ve attempted to show throughout this essay, we’ve had too much negative baggage to overcome for it to just be a fad.

Some dark-haired women accuse bleached women of self-hate and “selling out.” Bleached women go on the defensive, saying that bleaching is “just a choice.” Dark-haired women point out that if bleaching really were just a choice, then women who decide to go natural wouldn’t experience as much flack as they do for basically “bucking the system” and that many of the negatives associated with wearing naturally dark hair (as listed above) wouldn’t exist or, if they did exist, they wouldn’t be so closely tied with negative opinions directed towards such women’s overall character, beauty, and/or worthiness as human beings.

This would be a stronger point if I’d set up my scenario such that the majority of white people had naturally blonde hair and dark-haired white people were a minority group that regularly experienced discrimination for many years because of the color of their hair. As I said in the beginning, there’s a whole historical context behind black women relaxing their hair, which I’ve pretty much skirted for the purposes of this scenario.

I could go on, but I think I’ve made my point.

Let me reiterate: If every point I listed was true for white women and hair dye, only then could it be said that dyeing and relaxing were the same thing.

As I said at the beginning, in this scenario I’ve left out several important historical and cultural factors:

As enslaved people in the Americas, black people were stigmatized and dehumanized not only because of the color of their skin and the shape of their features, but because of the texture of their hair. Mixed-race people, usually (but not always) the children of slave masters and slave women, were often elevated in society and given privileges that darker-skinned, less European-looking blacks were denied. Some of these mixed-race people eventually created their own communities in which major tickets to admission involved the color of one’s skin (e.g. the paper bag test) and/or the texture of one’s hair (e.g. the fine-toothed comb test). Despite the 60s, when changes in hairstyling occurred as a response to this imposed stigmatization, this exclusionary, slavery-imposed categorization and valuation of hair textures has never been fully eliminated from the black consciousness. So even though white people pretty much started the stigmatization of Afro-textured hair, black folks picked up and ran with the ball not too long afterwards.

The European/American beauty standard not only emphasizes straight hair, but long straight hair. There’s a general belief in the black community that Afro-textured hair will not grow long on its own without some kind of help, and so many women will straighten their hair , add extensions, or wear weave just so they can have, or try to have the appearance of, long, flowing hair. Ironically, the chemicals that are used to straighten the hair to make it look long are the same chemicals that, if not used properly, will cause the hair to break off, which prevents length from occurring. The desire for and pursuit of long hair among black women is a whole other essay.

If you are black and you weren’t born with light skin or straight(er) hair, it’s a lot easier to straighten or cover up your hair than it is to lighten your skin. It’s the quickest and, relatively speaking, cheapest way to “fit in” with the European/American beauty standard.

Straightening, hiding, or covering up naturally tightly curled hair has become so common in the black community, particularly over the last 60 years or so, that even though the above three points are repeatedly stated, many black women who deep down don’t want to look at, deal with, or think about their natural hair defend their actions as “just a choice.” Given all the factors presented in my scenario, it should be obvious that these actions are really not “just a choice” and that most black women straighten, hide, or otherwise cover up their natural hair out of fear, shame, and/or lack of knowledge.

Things are changing. Some are finding that natural hair isn’t as bad as they were taught it was. Some who relax are looking for ways to reduce or eliminate their dependence on chemicals. More people are beginning to accept the wearing of natural Afro-textured hair as a choice, and from there, they’re beginning to see all the choices that are possible. Despite this, the vast majority of black women with Afro-textured hair still straighten their hair or cover it up with fake hair. And black women still spend far more money on their hair—largely in the pursuit of having something other than Afro-textured hair—than any other ethnic group. This is why the black hair care industry is a multimillion-dollar business and will continue to be so long as black women still believe, consciously, subconsciously, or unconsciously, that their Afro-textured hair is unacceptable.

Written by LBellatrix From Nappturality.com